Every day, for most of her life, Norma, a 68-year-old woman from the outskirts of Mexico City, has struggled to get something that many of us take for granted: drinking water.

She draws water from a well in her patio in Ecatepec, but it’s not fit for drinking. She can, however, use it for filling toilets, cleaning, or laundry. The water is unfiltered, she says, and it has caused her skin problems.

Though Norma is a widow, she is not alone. As Mexico City continues to expand while resources become scarce, its water crisis impacts millions. It exemplifies a future that cities worldwide could face if global warming and overpopulation continue. From springs that have been sealed or pipelined to rainwater that goes unused and into the drain, to drinking water that gets polluted or spilled on its way into homes across the megalopolis, many issues have created this crisis.

Norma lives by herself in a small house, which is sinking — another byproduct of the Mexican capital’s unquenchable thirst for water. According to Norma, the bedroom has already descended 20 inches below ground level. She feels constantly under stress, not just from poverty but also from the criminal groups prowling around her neighborhood. She refuses to provide her last name for this report, fearing retaliation.

Two hours away from Mexico’s capital, the water reservoir at the town of Valle de Bravo collects most of its water from nearby rivers and springs and is the main source for the Cutzamala water system. This system provides more than a quarter of Mexico City’s drinking water.

A complex network of about 45 miles of canals, 26 miles of tunnels, and six siphons, the Cutzamala system also has six pumping stations, 11 dams, 10 reservoirs, a major treatment plant, two storage reservoirs, and four storage reservoirs at the Mexico City terminal. Despite its complexity and engineering, it’s one of the key pivots in the city’s water crisis.

Prolonged overuse is one reason the lake has been so critically affected by drought. Agricultural demands, local consumption, and the city’s water needs have stretched its resources to a breaking point. Climate change has further exacerbated the situation, with erratic rainfall and extended dry seasons making it increasingly difficult to replenish the lake and ensure water stability.

The water scarcity has fueled social tensions as the Valle de Bravo community struggles to balance its own needs with the obligation to share water with Mexico City. In 2024, the town faced severe challenges due to dwindling water levels, and residents have had to adopt water-saving policies during drought seasons. They have also pushed the government to monitor the illegal diversion of creeks and rivers to wealthy, private properties and the building of unauthorized, restricted lagoons.

This crisis has also disrupted tourism, a cornerstone of the local economy. The reservoir lake has experienced some of the lowest levels in its history, making it harder for visitors to enjoy popular water sports in the area, such as skiing, flyboarding, paddle surfing, kayaking, sailing, and fishing. Angered Valle de Bravo inhabitants are pressuring authorities to regulate water usage for swimming pools on properties used mostly by tourists and property owners from big cities who vacation there.

Following months of severe drought in 2024, the late arrival of seasonal rains and emergency conservation measures such as localized rainwater harvesting brought some relief. The Cutzamala reservoir’s capacity increased to 67% in November 2024, up from 30% in May, according to data from Mexico’s National Water Commission. Government actions, including water rationing in Mexico City, likely contributed to this recovery. This increased capacity also provided temporary relief to the capital, which saw more consistent water distribution and fewer interruptions for urban areas. By February 2025, the reserve registered levels close to 61% of its capacity, which is still below the average levels of 72.3%, according to Valle de Bravo’s local water authorities.

In addition, wildfires have become an increasing threat to the area. In May 2024, several fires severely affected Valle de Bravo’s surrounding protected natural forests.

But the recovering water levels have not fully addressed concerns by communities around the reservoir, including Valle de Bravo, about resource depletion and inequitable water distribution. Residents remain wary of government priorities that seem to favor urban supply and wealthy real estate investors over the needs of local residents. And without sustainable practices and investments in the area’s water systems, the cycle of scarcity will persist, continuing to threaten livelihoods and lives.

Mexico City was built on top of what used to be a large body of water, which would make its water shortage appear ironic if it wasn’t so tragic. In the early 1300s, the Mexica (or Aztecs) settled on an island in the middle of what used to be a huge lake called Texcoco, the largest among five intertwined lakes.

But after the arrival of the Spaniards, the city started to expand, and the urban sprawl caused the lake system to dry up. By the early 20th century, the rivers feeding the once-rich lake zone were put into pipelines to make way for motor vehicles. Very little is left of the lakes, while the rivers have become practically invisible.

Groundwater, depleted by decades of overexploitation, along with the soft soil that used to be the lake bed, can no longer support the megalopolis. The sections of the city built on top of where the lakes used to be are literally sinking under their own weight.

The city’s sinking also causes major water leaks and spills, as underground pipelines fracture. Seismic activity, common in Mexico City, worsens the situation. Research from Mexico’s National Autonomous University indicates that 40% of Mexico City’s water is lost due to these spills.

“The settlement and historical development of this huge city, since pre-Columbian times, is in a closed basin on the bed of a lake,” says Hilda Hesselbach, a consultant for international development agencies in Mexico and a biologist specializing in nature conservation issues, including water preservation. “So, among the main problems of the water crisis come floods and, in part, differential sinking of the city due to compression of the ground.”

This is particularly evident in Mexico City’s historic downtown, where buildings and avenues buckle and tilt as they descend into the unstable soil. It also extends to nearby areas like the working-class suburbs of Ecatepec, where the problem is as glaringly obvious as Norma’s sunken bedroom.

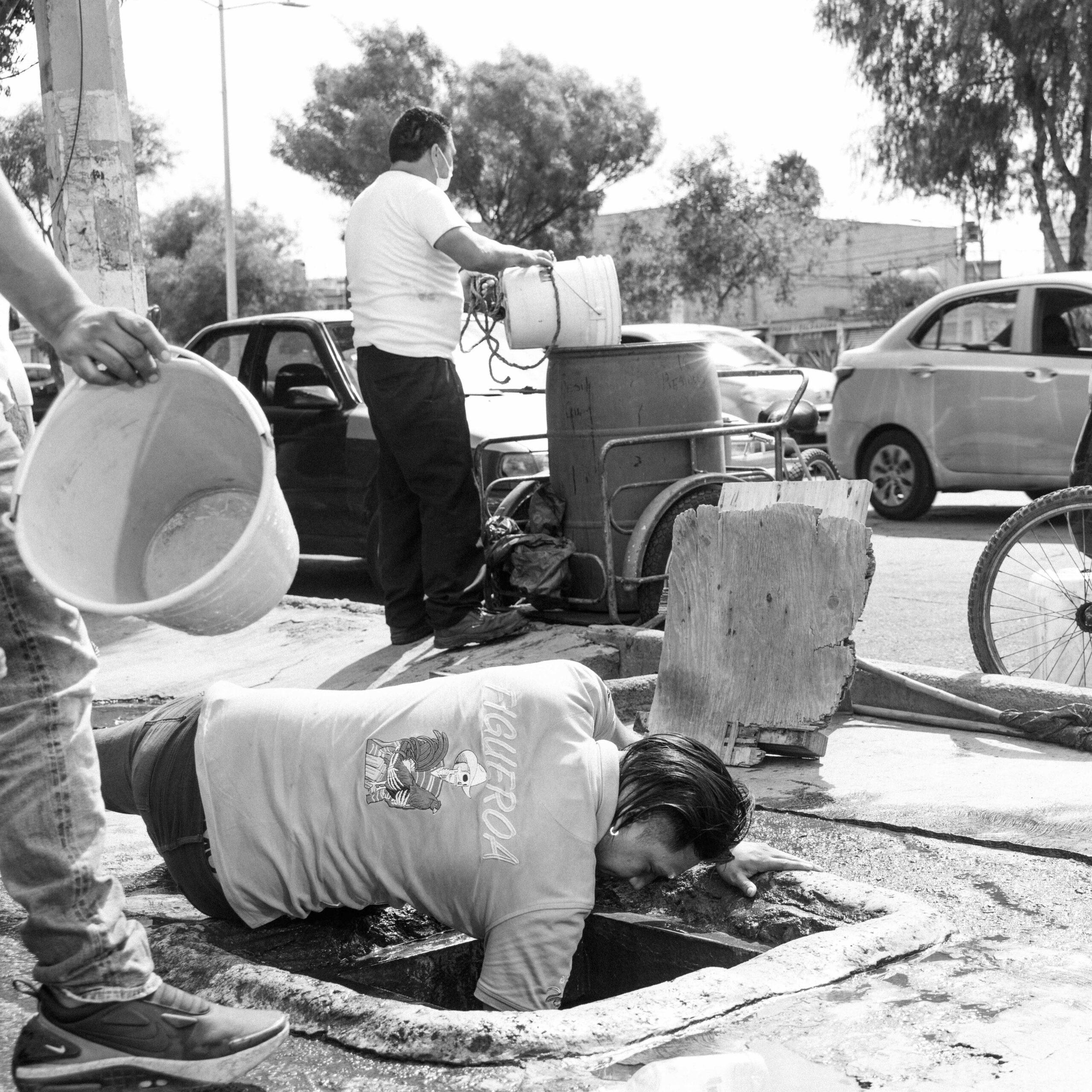

During Ecatepec’s tough drought seasons, taps run dry and running water becomes unavailable in the most impoverished areas, where residents draw water from public manholes and carry it away in plastic jerricans. But the area does get a significant amount of rain throughout the year (between 23 and 47 inches per annum), which is why nearly three-quarters of Mexico City’s water comes from underground wells and springs. “But since there has not been any real urban planning based on water, many of these groundwater recharge areas have been sealed off as a result of urban growth,” Hesselbach says.

“It’s an inefficient, not to say absurd, water management scheme,” she adds, citing poor administrative and planning systems with no effective current regulations. This leaves people like Norma to pull water from the ground wells without filtration, leading to skin and stomach diseases for those who use it.

And the scarcity elicits greed. Residents in some of Mexico City’s poorest neighborhoods have complained of being victimized by “huachicoleros,” a term usually used to describe people who steal gasoline for resale on the black market. Now this practice has extended to drinking water.

Taking advantage of the authorities’ lack of supervision, criminal groups steal water from public wells and pipes to sell it to local residents. This illicit trade is becoming increasingly profitable as droughts and infrastructure problems worsen.

A few miles north of Mexico City, Zumpango Lagoon, one of the few remnants of Lake Texcoco, was a popular local tourist destination until just a few years ago. But the lack of rain has seriously affected the water level, causing a significant reduction in its surface area. Once vibrant and full of activity, the lagoon went into a state of desolation. By March 2024, it had practically disappeared.

Zumpango is also part of the area affected by historic draining. Concrete and asphalt replaced wetlands and rivers, leading to seasonal extremes: floods in the rainy season and droughts during the dry months, which have worsened with climate change as high temperatures accelerate evaporation.

But for some experts, solutions exist. Better wastewater treatment could increase supply and reduce pollution. Rainwater harvesting systems could cut residents’ dependence on water trucks. Fixing leaks from the system could improve efficiency and reduce aquifer extraction. Restoring rivers and wetlands could not only supply and purify water but also cool and green the city.

“Perhaps I am being very optimistic, but I believe that by reversing some processes, it is possible to gain some margin of action that would help prevent very critical situations of shortage,” says Hesselbach. But the situation is delicate, she notes. “The protection of natural water sources (is important) because they are part of an irreplaceable process.”

By September 2024, Zumpango registered encouraging water levels, recovering 65% of its full capacity. Authorities claim to have administered water surplus from nearby dams to aid in recovery of the lagoon. Local boat rides for tourists have picked up again, offering hope to the local population.

On a two-hour drive north of Mexico City into the state of Hidalgo, a deserted road cracked by the heat leads to the Endhó Dam, where shepherds graze their sheep nearby on the broken soil.

The landscape at one point looked post-apocalyptic, barren, and bleached by the sun’s relentless glare. Wastewater from Mexico City and several nearby factories, hospitals, a refinery, and a thermoelectric power station have contaminated the dammed water and wells that supply 15,000 people in surrounding communities. In the municipality of Tepetitlán, stray dogs, as thin as shadows, shuffle along the dusty streets.

The artificial lake — or what was once an artificial lake — turned eventually into a thick, cracked layer of greenish sludge, emitting a stench that catches in the throat. The dam was even known by people in the area as “la cloaca más grande del mundo” — the world’s biggest sewer.

Jesús and Gloria have lived here all their lives. Both in their 50s and sheltering under an umbrella, they watch as their flock of sheep grazes on the poisoned grass. They say they barely notice the smell anymore.

Jesús points to spots on his hands that look like white plaster but is a medicinal ointment covering his sores. “The doctor says the sores are from the toxic chemicals dumped here,” he says.

Independent scientific reports say the nearby soil contains numerous toxic substances dumped by the region’s chemical plants that cause skin allergies among the residents. It contains heavy metals like lead and mercury, as well as arsenic, cyanide, nitrates, phosphorus, manganese, nickel, phosphates, oils, and detergents far beyond environmental limits. Some data suggests that at least two generations of local inhabitants have serious health issues, including cancer and kidney and lung diseases.

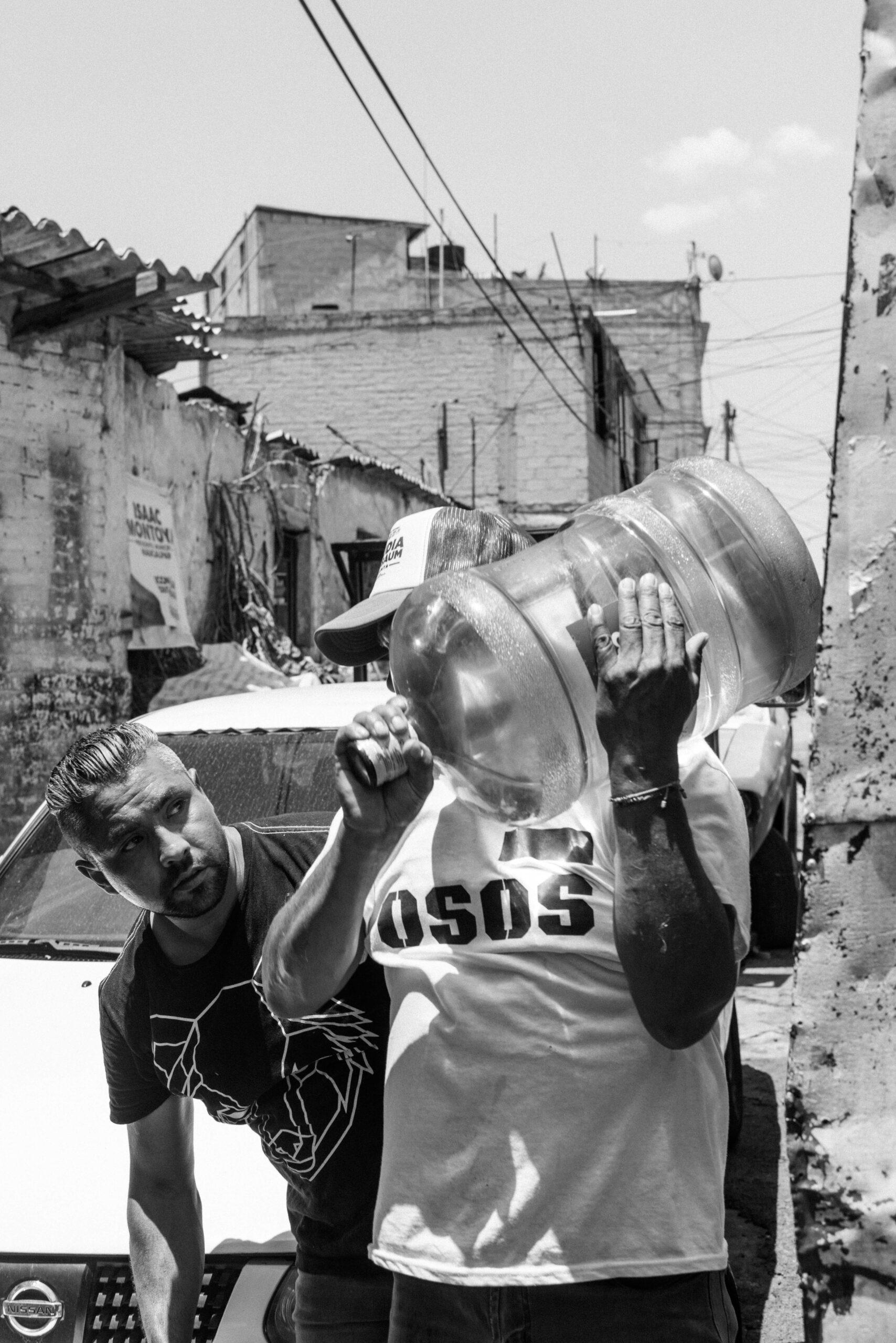

One of the communities hardest hit by the scarce water distribution is in Naucalpan de Juárez, a municipality northwest of Mexico City, whose residents have to constantly buy drinking water. There, a man identifying himself as Armando sells large bottles of water to those who can afford it. Each bottle, or “garrafón,” contains about 5 gallons of water, and sells for 100 pesos (about $5).

Armando says he visits the neighborhood on Tuesdays and Saturdays. With help from his son, he exchanges residents’ empty bottles for ones filled with drinking water, climbing in and out of the back of a small truck driven by his boss.

With the acceleration of global warming, weather phenomena like El Niño have brought unprecedented springtime heat waves to Mexico City.

Between May and June 2024, temperatures soared to 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius), the highest temperature recorded there in more than 100 years. This level of heat might sound pleasant when compared with temperatures in other major cities, but it’s unusual in a metropolis with almost no defined seasons and an average maximum temperature of 77 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius) per year.

This new heat is something Mexico City dwellers are learning to endure. With consistent, tempered heat and few small peaks of sweltering weather during the spring and early summer, most of the houses and buildings in Mexico City have no air conditioning. But now, it is more common for “chilangos” (inhabitants of Mexico City) to buy fans and install AC or other cooling systems in their homes or businesses.

And with this heat comes thirst and drought. The May 2024 heat wave created a large demand for water across the city, while supplies presented low levels and shortages in some areas. At spots where people would often go to cool off, like the Balneario Elba water park, just east of the city, some of the pools had been drained. Even ice-making companies reported shortages due to high demand from their overheated clientele and low production levels as their equipment struggled to freeze enough water.

South of the city, at the remains of Lake Xochimilco (one of the valley’s five original lakes), a sophisticated, pre-Columbian system of floating gardens extends the habitable surface of the lakes while creating fertile land for agriculture.

The agricultural islands, known as chinampas, were created over 2,000 years ago by Indigenous peoples of the Mexico City basin. Five hundred years after the fall of the Mexica Empire, Xochimilco’s floating gardens are still cultivated and produce food, flowers, and ornamental plants. In 2018, the United Nations designated this area a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System.

“These chinampas became the most productive food system in Mexico’s history, sustaining entire civilizations and proving that agriculture and ecology can coexist harmoniously,” says Johanna Hernández, a marketing director of Arca Tierra, a Mexican network dedicated to the sustainable production of food through regenerative agriculture and fair trade.

To reach the floating agricultural plots, one must cross their polluted surroundings with chaotic concrete sprawl and relentless traffic before venturing down the canals. Urban expansion and low farming incomes force some to abandon these traditional practices for more profitable ventures, like converting chinampas into residential plots.

“Today this vital agro-ecosystem is at serious risk. Urban pressure, abandonment, pollution, and the industrialization of the food system have led to only 20% of the 2,215 hectares (5,470 acres) of chinampas being actively cultivated,” says Hernández.

Preserving the chinampas is vital — not only for their cultural heritage but also for their role in supporting local biodiversity and regulating the urban climate. The gardens are home to one of Mexico’s richest hubs of biodiversity, including the most iconic species of Xochimilco, the axolotl, an endemic amphibian once abundant here. Today it is critically endangered, threatened by urban pressure, the destruction of chinampas, water shortages, climate warming, and pesticide contamination.

Local and international organizations like Arca Tierra fight to save this ecosystem and make it sustainable. Since 2009, this nonprofit has worked to ensure sustainability by supporting small-scale farmers socially, ecologically, and economically. It implements agroforestry techniques in Xochimilco to restore soil health and biodiversity, while improving water management by reducing evaporation and improving water retention.

Hernández says her organization envisions a day when chinampas will be appreciated as solutions rather than relics of the past. She says that by replicating their principles to address modern environmental challenges, wetland agriculture can help cities adapt to water scarcity and ensure local food security.

“Chinampas are a living example of how human intervention can be a force for good, fostering life and biodiversity. While it is often said that humans are the worst thing that has happened to the planet, Xochimilco proves otherwise. This system demonstrates that when we step away from centering ourselves in everything we can regenerate the world around us,” Hernández says.

“However, its future depends on collective action — from government agencies, private businesses, NGOs, and citizens alike,” she adds.